משתמש:MathKnight/אדריכלות רומנסקית

|

דף זה אינו ערך אנציקלופדי

| |

| דף זה אינו ערך אנציקלופדי | |

Vaults and roofs

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]The majority of buildings have wooden roofs, generally of a simple truss, tie beam or king post form. In the case of trussed rafter roofs, they are sometimes lined with wooden ceilings in three sections like those which survive at Ely and Peterborough cathedrals in England. In churches, typically the aisles are vaulted, but the nave is roofed with timber, as is the case at both Peterborough and Ely.[1] In Italy where open wooden roofs are common, and tie beams frequently occur in conjunction with vaults, the timbers have often been decorated as at San Miniato al Monte, Florence.[2]

Vaults of stone or brick took on several different forms and showed marked development during the period, evolving into the pointed ribbed arch which is characteristic of Gothic architecture.

Barrel vault

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]The simplest type of vaulted roof is the barrel vault in which a single arched surface extends from wall to wall, the length of the space to be vaulted, for example, the nave of a church. An important example, which retains Medieval paintings, is the vault of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, France, of the early 12th century. However, the barrel vault generally required the support of solid walls, or walls in which the windows were very small.[3]

Groin vault

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Groin vaults occur very frequently in earlier Romanesque buildings, and also for the less visible and smaller vaults in later buildings, particularly in crypts and aisles. A groin vault is almost always square in plan and is constructed of two barrel vaults intersecting at right angles. Unlike a ribbed vault, the entire arch is a structural member. Groin vaults are frequently separated by transverse arched ribs of low profile as at Santiago de Compostela. At La Madeleine, Vézelay, the ribs are square in section, strongly projecting and polychrome.[4]

Ribbed vault

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]

In ribbed vaults, not only are there ribs spanning the vaulted area transversely, but each vaulted bay has diagonal ribs. In a ribbed vault, the ribs are the structural members, and the spaces between them can be filled with lighter, none-structural material.

Because Romanesque arches are nearly always semi-circular, the structural and design problem inherent in the ribbed vault is that the diagonal span is larger and therefore higher than the transverse span. The Romanesque builders used a number of solutions to this problem. One was to have the centre point where the diagonal ribs met as the highest point, with the infil of all the surfaces sloping upwards towards it, in a domical manner. This solution was employed in Italy at San Michele, Pavia and Sant' Ambrogio, Milan.[3]

Another solution was to stilt the transverse ribs, or depress the diagonal ribs so that the centreline of the vault was horizontal, like a that of a barrel vault. The latter solution was used on the sexpartite vaults at both the Saint-Etienne, the Abbaye-aux-Hommes and Abbaye-aux-Dames at Caen, France, in the late 11th and early 12th centuries.[2]

Pointed arched vault

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Late in the Romanesque period another solution came into use for regulating the height of diagonal and transverse ribs. This was to use arches of the same diameter for both horizontal and transverse ribs, causing the transverse ribs to meet at a point. This is seen most notably at Durham Cathedral in northern England, dating from 1128. Durham is a cathedral of massive Romanesque proportions and appearance, yet its builders introduced several structural features which were new to architectural design and were to later to be hallmark features of the Gothic. Another Gothic structural feature employed at Durham is the flying buttress. However, these are hidden beneath the roofs of the aisles. The earliest pointed vault in France is that of the narthex of La Madeleine, Vézelay, dating from 1130.[5]

Church and cathedral plan and section

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]

Many parish churches, abbey churches and cathedrals are in the Romanesque style, or were originally built in the Romanesque style and have subsequently undergone changes. The simplest Romanesque churches are aisless halls with a projecting apse at the chancel end, or sometimes, particularly in England, a projecting rectangular chancel with a chancel arch that might be decorated with mouldings. More ambitious churches have aisles separated from the nave by arcades.

Abbey and cathedral churches generally follow the Latin Cross plan. In England, the extension eastward may be long, while in Italy it is often short or non-existent, the church being of T plan, sometimes with apses on the transept ends as well as to the east. In France the church of St Front, Perigueux, appears to have been modelled on St. Mark's Basilica, Venice or another Byzantine church and is of a Greek cross plan with five domes. In the same region, Angouleme Cathedral is an aisless church of the Latin cross plan, more usual in France, but is also roofed with domes.[3][2]

In Germany, Romanesque churches are often of distinctive form, having apses at both east and west ends, the main entrance being central to one side. It is probable that this form came about to accommodate a baptistery at the west end.[5]

In section, the typical aisled church or cathedral has a nave with a single aisle on either side. The nave and aisles are separated by an arcade carried on piers or on columns. The roof of the aisle and the outer walls help to buttress the upper walls and vault of the nave, if present. Above the aisle roof are a row of windows know as the clerestory, which give light to the nave. During the Romanesque period there was a development from this two-stage elevation to a three-stage elevation in which there is a gallery, known as a triforium, between the arcade and the clerestory. This varies from a simple blind arcade decorating the walls, to a narrow arcaded passage, to a fully-developed second story with a row of windows lighting the gallery.[3]

Church and cathedral east ends

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]

The eastern end of a Romanesque church is almost always semi-circular, with either a high chancel surrounded by an ambulatory as in France, or a square end from which an apse projects as in Germany and Italy. Where square ends exist in English churches, they are probably influenced by Anglo Saxon churches. Peterborough and Norwich Cathedrals have retained round east ends in the French style. However, in France, simple churches without apses and with no decorative features were built by the Cistercians who also founded many houses in England, frequently in remote areas.[6]

Buttresses

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Because of the massive nature of Romanesque walls, buttresses are not a highly significant feature, as they are in Gothic architecture. Romanesque buttresses are generally of flat square profile and do not project a great deal beyond the wall. In the case of aisled churches, barrel vaults, or half-barrel vaults over the aisles helped to buttress the nave, if it was vaulted.

In the cases where half-barrel vaults were used, they effectively became like flying buttresses. Often aisles extended through two storeys, rather than the one usual in Gothic architecture, so as to better support the weight of a vaulted nave. In the case of Durham Cathedral, flying buttresses have been employed, but are hidden inside the triforium gallery.[1]

Church and cathedral facades and external decoration

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Romanesque church facades, generally to the west end of the building, are usually symmetrical, have a large central portal made significant by its mouldings or porch and an arrangement of arched-topped windows. In Italy there is often a single central ocular window. The common decorative feature is arcading.[2]

Smaller churches often have a single tower which is usually placed to the western end, in France or England, either centrally or to one side, while larger churches and cathedrals often have two.

In France, Saint-Etienne, Caen presents the model of a large French Romanesque facade. It is a symmetrical arrangement of nave flanked by two tall towers each with two buttress of low flat profile which divide the facade into three vertical units. The three horizontal stages are marked by a large door set within an arch in each of the three vertical sections. The wider central section has two tiers of three identical windows, while in the outer tiers their are two tiers of single windows, giving emphasis to the mass of the towers. The towers rise through three tiers, the lowest of tall blind arcading, the next of arcading pierced by two narrow windows and the third of two large windows, divided into two lights by a colonette.[4]

This facade can be seen as the foundation for many other buildings, including both French and English Gothic churches. While the form is typical of northern France, its various components were common to many Romanesque churches of the period across Europe. Similar facades are found in Portugal. In England, Southwell Cathedral has maintained this form, despite the insertion of a huge Gothic window between the towers. Lincoln and Durham must once have looked like this. In Germany, the Limburger Dom has a rich variety of openings and arcades in horizontal storeys of varying heights.

The churches of San Zeno Maggiore, Verona and San Michele, Pavia present two types of facade that are typical of Italian Romanesque, that which reveals the architectural form of the building, and that which screens it. At San Zeno, the components of nave and aisles are made clear by the vertical shafts which rise to the level of the central gable and by the varying roof levels. At San Miniato al Monte the definition of the architectural parts is made even clearer by the polychrome marble, a feature of many Italian Medieval facades, particularly in Tuscany. At San Michele the vertical definition is present as at San Zeno, but the rooflines are screened behind a single large gable decorated with stepped arcading. At Santa Maria della Pieve, Arezzo this screening is carried even further, as the roofline is horizontal and the arcading rises in many different levels while the colonettes which support them have a great diversity of decoration.[5][7]

Towers

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Towers were an important feature of Romanesque churches and a great number of them are still standing. They take a variety of forms, square, circular and octagonal, and are positioned differently in relation to the church in different countries. In northern France, two large towers, such as those at Caen, were to become an integral part of the facade of any large abbey or cathedral. In central and southern France this is more variable and large churches may have one tower or a central tower. Large churches of Spain and Portugal usually have two towers.

Many abbeys of France, such as that at Cluny, had many towers of varied forms. This is also common in Germany, where the apses were sometimes framed with circular towers and the crossing surmounted by an octagonal tower as at Worms Cathedral. Large paired towers of square plan could also occur on the transept ends, such as those at Tournai Cathedral in Belgium. In Germany, where four towers frequently occur, they often have spires which may be four or eight sided, or the distinctive Rhenish helm shape seen on Limburg Cathedral.[3]

In England, for large abbeys and cathedral buildings, three towers were favoured, with the central tower being the tallest. This was often not achieved, through the slow process of the building stages, and in many cases the upper parts of the tower were not completed until centuries later as at Durham and Lincoln. Large Norman towers exist at the cathedrals of Durham, Exeter, Southwell and Norwich.[1]

In Italy towers are almost always free standing and the position is often dictated by the landform of the site, rather than aesthetics. This is the case in Italian nearly all churches both large and small, except in Sicily where a number of churches were founded by the Norman rulers and are more French in appearance.[2]

As a general rule, large Romanesque towers are square with corner buttresses of low profile, rising without diminishing through the various stages. Towers are usually marked into clearly defined stages by horizontal courses. As the towers rise, the number and size of openings increases as can be seen on the right tower of the transept of Tournai Cathedral where two narrow slits in the fourth level from the top becomes a single window, then two windows, then three windows at the uppermost level. This sort of arrangement is particularly noticeable on the towers of Italian churches, which are usually built of brick and may have no other ornament. Two fine examples occur at Lucca, at the church of San Frediano and at the Duomo. It is also seen in Spain.[2]

In Italy, there are a number of large free-standing towers which are circular, the most famous of these being the Leaning Tower of Pisa. In other countries where circular towers occur, such as Germany, they are usually paired and often flank an apse. Circular towers are uncommon in England, but occur throughout the Early Medieval period in Ireland.

Octagonal towers were often used on crossings and occur in France, Germany, Spain and Italy where an example that is unusual for its height is that on the crossing of Sant' Antonio, Piacenza, 1140.

In Spain, in the 12th century, a feature is the polygonal towers at the crossing. These have ribbed vaults and are elaborately decorated, such as the "Torre del Gallo" at Salamanca Old Cathedral.[3]

Decoration

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Architectural embellishment

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Arcading is the single most significant decorative feature of Romanesque architecture. It occurs in a variety of forms, from the Lombard band which is a row of small arches that appear to support a roofline or course, to shallow blind arcading often a feature of English architecture and seen in great variety at Ely Cathedral, to open galleries such as those on both Pisa Cathedral and its famous Leaning Tower. Arcades could be used to great effect, both externally and internally, as exemplified by the church of Santa Maria della Pieve, in Arezzo.[5]

Architectural sculpture

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]The Romanesque period produced a profusion of sculptural ornamentation. This most frequently took a purely geometric form and was particularly applied to mouldings, both straight courses and the curved moldings of arches. In La Madeleine, Vezelay, for example, the polychrome ribs of the vault are all edged with narrow filets of pierced stone. Similar decoration occurs around the arches of the nave and along the horizontal course separating arcade and clerestory. Combined with the pierced carving of the capitals, this gives a delicacy and refinement to the interior.[5]

In England, such decoration could be discrete, as at Hereford and Peterborough cathedrals, or have a sense of massive energy as at Durham where the diagonal ribs of the vaults are all outlined with chevrons, the mouldings of the nave arcade are carved with several layers of the same and the huge columns are deeply incised with a variety of geometric patterns creating an impression of directional movement. These features combine to create one of the richest and most dynamic interiors of the Romanesque period.[8]

Although much sculptural ornament was sometimes applied to the interiors of churches, the focus of such decoration was generally the west front, and in particular, the portals. Chevrons and other geometric ornaments, referred to by 19th century writers as "barbaric ornament" are most frequently found on the mouldings of the central door. Stylized foliage often appears, sometimes deeply carved and curling outward after the manner of the acanthus leaves on Corinthian capitals, but also carved in shallow relief and spiral patterns, imitating the intricacies of manuscript illuminations. In general, the style of ornament was more classical in Italy, such as that seen around the door of Sant Giusto in Lucca, and more "barbaric" in England, Germany and Scandinavia, such as that seen at Speyer Cathedral. France produced a great range of ornament, with particularly fine interwoven and spiralling vines in the "manuscript" style occurring at Saint-Sernin, Toulouse.[5][9][3]

Figurative sculpture

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]

With the fall of the Roman Empire, the tradition of carving large works in stone and sculpting figures in bronze died out, as it effectively did (for religious reasons) in the Byzantine world. Some life-size sculpture was evidently done in stucco or plaster, but surviving examples are understandably rare.[10] The best-known surviving large sculptural work of Proto-Romanesque Europe is the life-size wooden Crucifix commissioned by Archbishop Gero of Cologne in about 960–65.[11] During the 11th and 12th centuries, figurative sculpture flourished. It was based on two other sources in particular, manuscript illumination and small-scale sculpture in ivory and metal. The extensive friezes sculpted on Armenian and Syriac churches are have been proposed as another likely influence.[12] These sources together produced a distinct style which can be recognised across Europe, although the most spectacular sculptural projects are concentrated in South-Western France, Northern Spain and Italy.

Images that occurred in metalwork were frequently embossed. The resultant surface had two main planes and details that were usually incised. This treatment was adapted to stone carving and is seen particularly in the tympanum above the portal, where the imagery of Christ in Majesty with the symbols of the Four Evangelists is drawn directly from the gilt covers of medieval Gospel Books. This style of doorway occurs in many places and continued into the Gothic period. A rare survival in England is that of the "Prior's Door" at Ely Cathedral. In South-Western France, many have survived, with impressive examples at Saint-Pierre, Moissac, Souillac,[13] and La Madaleine, Vézelay – all daughter houses of Cluny, with extensive other sculpture remaining in cloisters and other buildings. Nearby, Autun Cathedral has a Last Judgement of great rarity in that it has uniquely been signed by its creator, Giselbertus.[7][5]

A feature of the figures in manuscript illumination is that they often occupy confined spaces and are contorted to fit. The custom of artists to make the figure fit the available space lent itself to a facility in designing figures to ornament door posts and lintels and other such architectural surfaces. The robes of painted figures were commonly treated in a flat and decorative style that bore little resemblance to the weight and fall of actual cloth. This feature was also adapted for sculpture. Among the many examples that exist, one of the finest is the figure of the Prophet Jeremiah from the pillar of the portal of the Abbey of Saint-Pierre, Moissac, France, from about 1130.[5]

One of the most significant motifs of Romanesque design, occurring in both figurative and non-figurative sculpture is the spiral. One of the sources may be Ionic capitals. Scrolling vines were a common motif of both Byzantine and Roman design, and may be seen in mosaic on the vaults of the 4th century Church of Santa Costanza, Rome. Manuscripts and architectural carvings of the 12th century have very similar scrolling vine motifs.

Another source of the spiral is clearly the illuminated manuscripts of the 7th to 9th centuries, particularly Irish manuscripts such as the St. Gall Gospel Book, spread into Europe by the Hiberno-Scottish mission. In these illuminations the use of the spiral has nothing to do with vines or other natural growth. The motif is abstract and mathematical. It is in an adaptation of this form that the spiral occurs in the draperies of both sculpture and stained glass windows. Of all the many examples that occur on Romanesque portals, one of the most outstanding is that of the central figure of Christ at La Madaleine, Vezelay.[5] Another influence from Insular art are engaged and entwined animals, often used to superb effect in capitals (as at Silos) and sometimes on a column itself (as at Moissac).

Many of the smaller sculptural works, particularly capitals, are Biblical in subject and include scenes of Creation and the Fall of Man, episodes from the life of Christ and those Old Testament scenes which prefigure his Death and Resurrection, such as Jonah and the Whale and Daniel in the Lions' Den. Many Nativity scenes occur, the theme of the Three Kings being particularly popular. The cloisters of Santo Domingo de Silos Abbey in Northern Spain, and Moissac are fine examples surviving complete.

A feature of some Romanesque churches is the extensive sculptural scheme which covers the area surrounding the portal or, in some case, much of the facade. Angouleme Cathedral in France has a highly elaborate scheme of sculpture set within the broad niches created by the arcading of the facade. In Spain, an elaborate pictorial scheme in low relief surrounds the door of the church of Santa Maria at Ripoli.[5]

The purpose of the sculptural schemes was to convey a message that the Christian believer should recognise their wrong-doings, repent and be redeemed. The Last Judgement reminds the believe to repent. The carved or painted Crucifix, displayed prominently within the church, reminded the sinner of their redemption. The sculpture which reminded the sinners of their sins often took alarming forms. These sculptures, not being of Christ, were usually not large and are rarely magnificent, but are often fearsome or simply entertaining in nature.

These are the works that frequently decorate the smaller architectural features. They are found on capitals, corbels and bosses, or entwined in the foliage on door mouldings. They represent the Seven Deadly Sins but often take forms that are not easily recognisable today. Lust, gluttony and avarice are probably the most frequently represented. The appearance of many figures with oversized genitals can clearly be equated with carnal sin, but so also can the numerous figures shown with protruding tongues, which are a feature of the doorway of Lincoln Cathedral. Pulling ones beard was a symbol of masturbation, and pulling ones mouth wide open was also a sign of lewdity. A common theme found on capitals of this period is a tongue poker or beard stroker being beaten by his wife or seized by demons. Demons fighting over the soul of a wrongdoer such as a miser is another popular subject.[14]

Gothic architecture is usually considered to begin with the design of the choir at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, north of Paris, by the Abbot Suger, consecrated 1144. The beginning of Gothic sculpture is usually dated a little later, with the carving of the figures around the Royal Portal at Chartres Cathedral, France, 1150–55. The style of sculpture spread rapidly from Chartres, overtaking the new Gothic architecture. In fact, many churches of the late Romanesque period post-date the building at Saint-Denis. The sculptural style based more upon observation and naturalism than on formalised design developed rapidly. It is thought that one reason for the rapid development of naturalistic form was a growing awareness of Classical remains in places where they were most numerous and a deliberate imitation of their style. The consequence is that there are doorways which are Romanesque in form, and yet show a naturalism associated with Early Gothic sculpture.[5]

One of these is the Pórtico da Gloria dating from 1180, at Santiago de Compostela. This portal is internal and is particularly well preserved, even retaining colour on the figures and indicating the gaudy appearance of much architectural decoration which is now perceived as monochrome. Around the doorway are figures who are integrated with the colonnettes that make the mouldings of the doors. They are three dimensional, but slightly flattened. They are highly individualised, not only in appearance but also expression and bear quite strong resemblance to those around the north porch of the Abbey of St. Denis, dating from 1170. Beneath the tympanum there is a realistically carved row of figures playing a range of different and easily identifiable musical instruments.

Murals

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]The large wall surfaces and plain, curving vaults of the Romanesque period leant themselves to mural decoration. Unfortunately, many of these early wall paintings have been destroyed by damp or the walls have been replastered and painted over. In England, France and the Netherlands such pictures were systematically destroyed in bouts of Reformation iconoclasm. In other countries they have suffered from war, neglect and changing fashion.

A classic scheme for the full painted decoration of a church, derived from earlier examples often in mosaic, had, as its focal point in the semi-dome of the apse, Christ in Majesty or Christ the Redeemer enthroned within a mandorla and framed by the four winged beasts, symbols of the Four Evangelists, comparing directly with examples from the gilt covers or the illuminations of Gospel Books of the period. If the Virgin Mary was the dedicatee of the church, she might replace Christ here. On the apse walls below would be saints and apostles, perhaps including narrative scenes, for example of the saint to whom the church was dedicated. On the sanctuary arch were figures of apostles, prophets or the twenty-four "elders of the Apocalypse", looking in towards a bust of Christ, or his symbol the Lamb, at the top of the arch. The north wall of the nave would contain narrative scenes from the Old Testament, and the south wall from the New Testament. On the rear west wall would be a Last Judgement, with an enthroned and judging Christ at the top.[15]

One of the most intact schemes to exist is that at Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe in France. The long barrel vault of the nave provides an excellent surface for fresco, and is decorated with scenes of the Old Testament, showing the Creation, the Fall of Man and other stories including a lively depiction of Noah's Ark complete with a fearsome figurehead and numerous windows through with can be seen the Noah and his family on the upper deck, birds on the middle deck, while on the lower are the pairs of animals. Another scene shows with great vigour the swamping of Pharaoh's army by the Red Sea. The scheme extends to other parts of the church, with the martyrdom of the local saints shown in the crypt, and Apocalypse in the narthex and Christ in Majesty. The range of colours employed is limited to light blue-green, yellow ochre, reddish brown and black. Similar paintings exist in Serbia, Spain, Germany, Italy and elsewhere in France.[3]

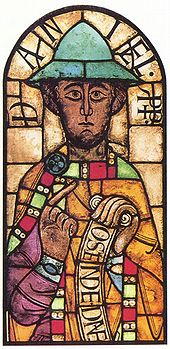

Stained glass

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]The oldest-known fragments of medieval pictorial stained glass appear to date from the 10th century. The earliest intact figures are five prophet windows at Augsburg, dating from the late 11th century. The figures, though stiff and formalised, demonstrate considerable proficiency in design, both pictorially and in the functional use of the glass, indicating that their maker was well accustomed to the medium. At Canterbury and Chartres Cathedrals, a number of panels of the 12th century have survived, including, at Canterbury, a figure of Adam digging, and another of his son Seth from a series of Ancestors of Christ. Adam represents a highly naturalistic and lively portrayal, while in the figure of Seth, the robes have been used to great decorative effect, similar to the best stone carving of the period.

Most of the magnificent stained glass of France, including the famous windows of Chartres, date from the 13th century. Far fewer large windows remain intact from the 12th century. One such is the Crucifixion of Poitiers, a remarkable composition which rises through three stages, the lowest with a quatrefoil depicting the Martyrdom of St Peter, the largest central stage dominated by the crucifixion and the upper stage showing the Ascension of Christ in a mandorla. The figure of the crucified Chirst is already showing the Gothic curve. The window is described by George Seddon as being of "unforgettable beauty".[16]

Transitional style

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]During the 12th century, features that were to become typical of Gothic architecture began to appear. It is not uncommon, for example, for a part of building that has been constructed over a lengthy period extending into the 12th century, to have very similar arcading of both semi-circular and pointed shape, or windows that are identical in height and width, but in which the later ones are pointed. This can be seen on the towers of Tournai Cathedral and on the western towers and facade at Ely Cathedral. Other variations that appear to hover between Romanesque and Gothic occur, such as the facade designed by Abbot Suger at the Abbey of Saint-Denis which retains much that is Romanesque in its appearance, and the Facade of Laon Cathedral which, despite its Gothic form, has round arches.[1][17]

Romanesque influence

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Paris and its surrounding area were quick to adopt the Gothic style of Abbot Suger Abbey of Saint-Denis in the 12th century but other parts of France were slower to take it up, and provincial churches continued to be built in the heavy manner and rubble stone of the Romanesque, even when the openings were treated with the fashionable pointed arch.

In England, the Romanesque groundplan, which in that country commonly had a very long nave, continued to affect the style of building of cathedrals and those large abbey churches which were also to become cathedrals in the 16th century. Despite the fact that English cathedrals were rebuilt in many stages, substantial areas of Norman building can be seen in many of them, particularly in the nave arcades. In the case of Winchester Cathedral, the Gothic arches were literally carved out of the existent Norman piers.[1]

In Italy, although many churches such as Florence Cathedral and Santa Maria Novella were built in the Gothic style, sturdy columns with capitals of a modified Corinthian form continued to be used. The pointed vault was utilised where convenient, but it is commonly interspersed with semicircular arches and vaults wherever they conveniently fit. The facades of Gothic churches in Italy are not always easily distinguishable from the Romanesque.

Germany was not quick to adopt the Gothic style, and when it did so, often the buildings were modelled very directly upon French cathedrals, as Cologne Cathedral was modelled on Amiens. The smaller churches and abbeys continued to be constructed in a more provincial Romanesque manner, the date only being registered by the pointed window openings.[5]

מבנים ראויים לציון

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]הרבה מאוד כנסיות בסגנון הרומנסקי נמצאות בצרפת (בדגש על צפון צרפת וחבל נורמנדי בפרט) ובצפון ספרד. כנסיות רבות נוספות נמצאות גם בגרמניה, אנגליה, אירלנד וצפון איטליה. קיימות גם כנסיות רומנסקיות במדינות נוספות באירופה באזור ארצות השפלה, סקנדינביה מרכז אירופה ופולין. בכל ארץ הסגנון התאפיין באלמנטים מקומיים מעט שונים. בישראל על פסגת הר תבור שוכנת כנסייה רומנסקית, כנסיית ההשתנות.

צרפת

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]- קתדרלת אוטן, בורגון

- כנסיית סן-סרנין, טולוז

- כנסיית נוטרדאם-די-פור, קלרמון-פראן (Notre-Dame-du-Port, Clermont-Ferrand)

- כנסיית סן סאבאן סור גארטאן (Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe)

ספרד

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]- קתדרלת סנטיאגו דה קומפוסטלה וכנסיות רבות על מסלול העלייה לרגל לסנטיאגו באזור צפון ספרד.

בלגיה

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]אנגליה

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]גרמניה

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]איטליה

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]Romanesque Revival

[עריכת קוד מקור | עריכה]During the 19th century, when Gothic Revival architecture was fashionable, buildings were occasionally designed in the Romanesque style. There are a number of Romanesque Revival churches, dating from as early as the 1830s and continuing into the 20th century where the massive and "brutal" quality of the Romanesque style was appreciated and designed in brick.

The Natural History Museum, London designed by Alfred Waterhouse, 1879, on the other hand, is a Romanesque revival building which makes full use of the decorative potential of Romanesque arcading and architectural sculpture. The Romanesque appearance has been achieved while freely adapting an overall style to suit the function of the building. The columns of the foyer, for example, give an impression of incised geometric design similar to those of Durham Cathedral. However, the sources of the incised patterns are the trunks of palms, cycads and tropical tree ferns. The animal motifs, of which there are many, include rare and exotic species.

The type of modern buildings for which the Romanesque style was most frequently adapted was the warehouse, where a lack of large windows and an appearance of great strength and stability were desirable features. These buildings, generally of brick, frequently have flattened buttresses rising to wide arches at the upper levels after the manner of some Italian Romanesque facades. This style was adapted to suit commercial buildings by opening the spaces between the arches into large windows, the brick walls becoming a shell to a building that was essentially of modern steel-frame construction, the architect Henry Hobson Richardson giving his name to the style, "Richardson Romanesque". Good examples of the style are Marshall Fields store, Chicago by H.H.Richardson, 1885, and the Chadwick Lead Works in Boston USA by William Preston, 1887. The style also lent itself to the building of cloth mills, steelworks and powerstations.[4][2]

- ^ 1 2 3 4 5 טקסט ההערה

- ^ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 טקסט ההערה

- ^ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 טקסט ההערה

- ^ 1 2 3 Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture

- ^ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 טקסט ההערה

- ^ F.H.Crossley, The English Abbey.

- ^ 1 2 טקסט ההערה

- ^ Alec Clifton-Taylor says "With the Cathedral of Durham we reach the incomparable masterpiece of Romanesque architecture not only in England but anywhere."

- ^ טקסט ההערה

- ^ Some (probably) 9th century near life-size stucco figures were discovered behind a wall in Santa Maria in Valle, Cividale del Friuli in Northern Italy relatively recently. Atroshenko and Collins p. 142

- ^ See details at Cologne Cathedral.

- ^ V.I. Atroshenko and Judith Collins, The Origins of the Romanesque,p. 144–50, Lund Humphries, London, 1985, ISBN 085331487X

- ^ Howe, Jeffery. "Romanesque Architecture (slides)". A digital archive of architecture. Boston College. נבדק ב-2007-09-28.

- ^ "Satan in the Groin". beyond-the-pale. נבדק ב-2007-09-28.

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p154, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0719539714

- ^ George Seddon in Lee, Seddon and Stephens, Stained Glass

- ^ Wim Swaan, Gothic Cathedrals